Why Do People Start Wars?

“The constitution supposes, what the History of all Governments demonstrates, that the Executive is the branch of power most interested in war, and most prone to it. It has accordingly with studied care, vested the question of war in the Legislature.” – James Madison (1798), in a letter to Thomas Jefferson

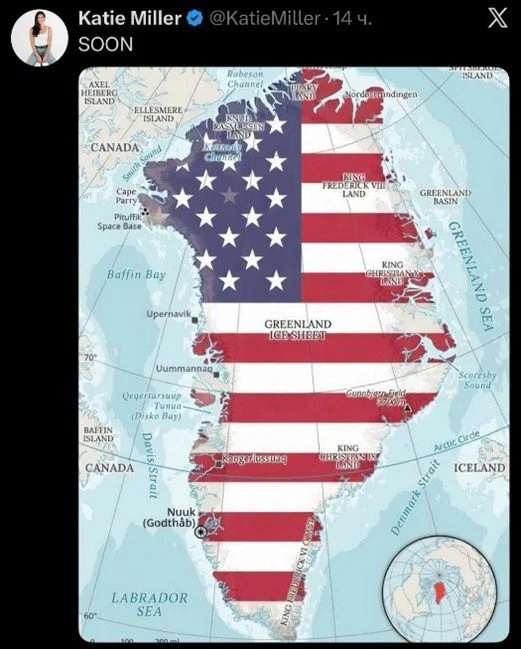

Posted 1/3/26 on X by Katie Miller, wife of Stephen Miller, one of President Trump’s most influential aides

(Agence France-Presse, 2026)

Most wars begin for a mix or perhaps a muddle of reasons, but the basic energies behind them, I believe, are the following.

Wars of Fear. You might go to war because you worry about a neighbor, and want to get them before they get you. In 1967, Israel’s neighbors were gearing up to attack her, so she attacked them first. Rome’s experience with Hannibal in the Second Punic War led to Cato ending each of his speeches in the Roman Senate with “Carthage must be destroyed.” Often, when a nation appears to be getting too powerful, others will try to cut it down to size: that was the fundamental reason why Sparta fought Athens in the Peloponnesian War, and why Britain fought Germany in 1914. Wars to preserve a balance of power are, at bottom, Wars of Fear, although that fear is not necessarily irrational.

Wars of Anger. You might lash out to avenge a perceived injustice, defeat, or humiliation, especially the latter: no one is more inclined to violence than a person who has just been humiliated. The Persian king Xerxes invaded Greece to avenge his father’s loss to the Athenians at the Battle of Marathon. Hitler wanted to avenge Germany’s defeat in 1919. The Arab-Israeli conflict has been fueled by the Arabs’ numerous humiliations in their wars with Israel. The United States lashed back at its attackers after Pearl Harbor and 9/11. Of course, some of these angers will seem to an onlooker more justified than others.

Wars of Plunder. Ambitious Romans – Pompey, Crassus, Julius Caesar – would invade territories to acquire loot for both their country and themselves. Colonial wars are generally about plunder, as was Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Since such a war is essentially nationalized robbery, those who start one will generally try, at least in modern times, to describe it as something else.

Wars of Ego. Historically, the best way to acquire the sobriquet “the Great” – Cyrus the Great, Alexander the Great, Pompey the Great, Alfred the Great, Charlemagne (Charles the Great), Frederick the Great – has been through military victory. Alexander had some practical reasons for attacking Persia – among other things, there was plenty to loot – but the only reason for many of his campaigns was a desire to find new worlds to conquer. In autocracies, Wars of Ego are extremely common. From Caesar to Louis XIV to Napoleon to Kaiser Wilhelm to Adolf Hitler to Vladimir Putin, if you are a ‘man of power,’ the expansion of your nation’s power, and thus of your own, can easily become a driving passion.

As the Madison quote above indicates, the U.S. Constitution was partly designed to prevent America from being ruled by an Alexander or a Caesar. The Founders did not want American citizens to die for one man’s vainglory; they thought we should go to war only if it was the will of the people, and so they vested the warmaking power in Congress. Since fighting a war through rule-by-committee was known to be inefficient, and since everyone knew George Washington would end up with the job, the President was designated Commander-in-Chief, but his brief was to execute the will of Congress. They were supposed to decide when and where we would fight. The President was only put in charge of the ‘how.’

The War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II – i.e. all of our major foreign conflicts up through 1945, with the exception of the Civil War, which the government was unwilling to label a “foreign conflict” – were accompanied by Declarations of War, as the Founders intended. But all that changed after World War II.

Harry Truman never asked for a Declaration of War against North Korea, because he was afraid it would escalate, 1914-style, into war with Communist China and the Soviet Union. For legal cover he used a U.N. Security Council resolution and called what was happening “a police action.” One can sympathize with Truman’s desire to avoid World War III, but it did set an unfortunate precedent: Congress’s constitutional role was circumvented, and things stopped being called by their true names. Korea was our first big undeclared foreign war, but it was not our last. Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq all received some form of Congressional authorization, but in spite of their scope – Afghanistan and Vietnam were the longest-running wars in U.S. history – none of them either began with or was accompanied by a Declaration of War.

That this became our pattern after World War II is no coincidence. That was when we became a world empire, and a world empire is constantly using power – a little here, a little there – to sustain its far-flung structures. To exert influence beyond one’s borders means using the military and the quasi-military (e.g. the CIA) in non-transparent ways. Empire is exploitative, secretive, and ruthless, and its use of military force tends to share those qualities.

Besides America’s major wars, there have been dozens, probably hundreds, of smaller military actions which presidents have initiated on their own. Among the relatively recent ones, there was the invasion of Grenada, under Ronald Reagan; of Panama, under George H.W. Bush; the bombing of Serbia, under Bill Clinton; and of Libya, under Barack Obama. Some of these incursions may have been more virtuous than others, but all of them were decisions taken exclusively within the executive branch. The War Powers Act of 1973, a response to Vietnam, was meant to claw back the warmaking prerogative to Congress, but that act allows presidents take unilateral military action for up to sixty days, and because it isn’t easy politically to cut off funding to troops in the field, “the War Powers Act has never been successfully employed to end any military mission” (Greenblatt, 2011).

In this context, what are we to make of President Trump’s military actions against Venezuela, including the kidnapping of its president, Nicolas Maduro, and his wife?

The first thing to notice is that these actions were entirely one man’s decision. If either the Congress or the American people had any desire to attack Venezuela, they’ve done an excellent job of concealing it. Congress, both of whose houses are controlled by the President’s own party, not only did not consent, but was not even consulted beforehand, although, according to the President, American oil companies were (Fortinsky, 2011). (The oil companies deny this.) Venezuela did not attack us, and obviously poses no military threat to the United States.

Are they some other kind of threat? The administration has accused the Maduros of being “narco-terrorists,” and by all accounts they are involved in the international cocaine trade, but Venezuela seems to be a transit country, not a producer, and most of its drugs go to Europe (Glatsky & Correal, 2026). Furthermore, Trump recently pardoned a former president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernandez, who was convicted of shipping more than 400 tons of cocaine into the United States (Biase, Scarff & Wratchford, 2024). Maduro seems to be corrupt and noxious, but that hardly makes him unique among world leaders. All in all, it’s hard to see how this could be called a War of Fear.

Is it a War of Anger? Donald Trump is good at anger – he constantly feels slighted, and that no one gives him as much of anything as he deserves – but if Maduro has called him names, well, so has much of the rest of the world. In 2007, Venezuela nationalized its energy industry and kicked out some U.S. oil companies, but so have quite a few other countries – Mexico, Bolivia, Iran, Russia – and we haven’t kidnapped their presidents, at least not yet.

Perhaps this is what one might call a charitable war, prompted by compassion for the Venezuelan people, for whom the Maduro Era has not exactly been a golden age? Trump does not as a rule concern himself with the sufferings of foreigners, and when in 2016 the Department of Defense war-gamed what would happen if Maduro were forcibly removed from power, they concluded that Venezuela would most likely fall into chaos and civil war (Crowley, 2025). The Chinese have a saying that one day of anarchy is worse than a year of tyranny, and if Venezuela becomes a failed state, its populace will have gone out of the frying pan into the fire.

For years, Trump has claimed to be a president who avoids wars, and who deserves the Nobel Peace Prize for ending them. So what’s going on here?

In the absence of other plausible motives, we must discuss Venezuela’s oil reserves, which are thought to be the largest in the world (Worldometer, n.d.). Trump talked extensively about them at his post-invasion press conference: he said American oil companies would “be taking out a tremendous amount of wealth out of the ground” (Troianovski, 2026). He has talked before about grabbing back what Venezuela nationalized in 2007.

“If you remember, they took all of our energy rights; they took all of our oil from not that long ago,” Mr. Trump said last month. “And we want it back.” (Troianovski, 2026)

Trump has also talked in a similar way about oil reserves in the Middle East.

“I’ve been saying it for years. Take the oil,” he told The New York Times in 2016, when asked how his strategy to fight the Islamic State in the Middle East would differ from President Barack Obama’s approach. (Troianovski, 2026)

All of this makes our attack on Venezuela sound a lot like a War of Plunder. Traditionally the U.S. has opposed such wars, which, in addition to their moral dubiousness, are deeply destabilizing, and thus bad for international business. That, for instance, was why we pushed back against Saddam Hussein’s occupation of Kuwait. Furthermore, history teaches that Wars of Plunder have a lot of ways to go wrong, because when you show a proclivity to steal other people’s stuff, they tend to band against you. Even if you think the powerful should grab what they want – a worldview that seems to have been endorsed a few days ago by Stephen Miller in an interview on CNN[1] – you might want to consider the possible pitfalls. If Venezuela does fall into chaos, it will become a tough place to “drill, baby, drill,” and if we insist on doing so, we will probably need to station American troops, or at least mercenaries, in a place where hostile locals will have many incentives to try to kill them. Occupying a country riven by domestic insurgencies – we learned how much fun that was in Iraq. And probably for that reason, as well as because of a current worldwide oil glut, American energy companies do not seem to be champing at the bit to go back into Venezuela (Domonoske, 2026).

Oil isn’t the only plunder which the President seems to covet. Greenland – the subject of Stephen Miller’s wife’s recent post, reproduced at the top of this piece – is rich in rare earth minerals (REM), which, because of environmental concerns, are difficult to mine in the U.S., and are crucial to many emerging technologies, including ones dear to the heart of Elon Musk, with whom Trump is evidently once again on good terms (Dwoskin, Allison & Siddiqui, 2025). Although the President claims we need Greenland “from the standpoint of national security” (Bennett, 2026), it already belongs to a NATO ally, and we are already the only foreign power with a military base there. A more plausible reason for his interest is that Greenland has (a) plentiful deposits of REM, and (b) not many people – and no American voters – to complain about the environmental damage involved in extracting them. A hunger for rare earth minerals is a theme for this administration. Trump has demanded them from Ukraine in return for our military aid (Reuters, 2025), and Canada’s deposits of REM, as well as a vast array of other natural resources, seem to be at the core of his musings about making her our 51st state (Zurcher, 2025).

If Venezuela seems like one War of Plunder, Katie Miller’s post appears to predict another. Of course Wars of Plunder and Wars of Ego frequently overlap. Wealth and conquest are both ways to feel Big, and if Donald Trump has shown one constant in his life, it is an all-consuming need to feel Big. Such a person is always looking – is addicted to looking – for ways to project and expand his own power, and sooner or later, domestic boundaries will start to seem too small to him.

Historically, the only way to avoid the world described by Stephen Miller – a world in which, to paraphrase Thuycidides, the strong take what they want, and the weak suffer what they must – is to inscribe democratically-legislated constraints into a rule of law. Since 1945, the United States has been the bulwark of a rules-based international order which, compared to most historical epochs, has done a pretty good job – not a perfect job, but a pretty good one – of preventing Wars of Plunder and Wars of Ego. Do we really want to reverse that? Do we really want to become a nation of bullies and thieves? Do we want to live in Stephen Miller’s world, or in James Madison’s? What do we want the United States of America to be about?

~ STUDEBAKER (Studebaker@studebakerguy.bsky.com)

References

Agence France-Presse. (2026, January 5). Greenland slams ‘disrespectful’ pic posted by Trump aide’s wife. GMA News Online. https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/world/971633/greenland-slams-disrespectful-pic-posted-by-trump-aide-s-wife/story/#google_vignette

Bennett, T. (2026, January 6). Which countries could be in Trump's sights after Venezuela? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cd0ye72r4vpo

Biase, N., Scarff, L., & Wratchford, S. (2024). Juan Orlando Hernandez, former President of Honduras, sentenced to 45 years in prison for conspiring to distribute more than 400 tons of cocaine and related firearms offenses. United States Attorney's Office, Southern District of New York. https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/juan-orlando-hernandez-former-president-honduras-sentenced-45-years-prison-conspiring

Crowley, M. (2025, November 20). U.S. ran a war game on ousting Maduro. Venezuela fell into chaos. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/20/us/politics/venezuela-maduro-fallout-trump.html?searchResultPosition=4

Domonoske, C. (2026, January 7). The world has too much oil right now. Will companies want Venezuela's? NPR. https://www.npr.org/2026/01/07/nx-s1-5668491/venezuela-oil-global-markets#:~:text=Right%20now%2C%20companies%20are%20asking,to%20process%20this%20tricky%20oil

Dwoskin, E., Allison, N., & Siddiqui, F. (2025, December 29). How Vance brokered a truce between Trump and Musk. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/12/29/musk-trump-vance-maga-alliance/

Fortinsky, S. (2026, January 5). Trump says he tipped off oil companies on Venezuela attack. The Hill. https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/5672735-trump-venezuela-oil-industry/#:~:text=by%20Sarah%20Fortinsky%20%2D%2001/05,wealth%20out%20of%20the%20ground.%E2%80%9D

Glatsky, G., & Correal, A. (2026, January 3). The U.S. indictment of Maduro cites cocaine smuggling. Venezuela’s role in the trade is believed to be modest. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/03/world/americas/venezuela-drug-trade.html#:~:text=Cites%20Cocaine%20Smuggling.-,Venezuela's%20Role%20in%20the%20Trade%20Is%20Believed%20to%20Be%20Modest,and%20conspiracy%20to%20import%20cocaine

Greenblatt, A. (2011, June 16). Why the War Powers Act doesn't work. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2011/06/16/137222043/why-the-war-powers-act-doesnt-work#:~:text=The%201973%20law%20was%20meant,on%20who's%20deploying%20the%20troops.%22&text=The%20law%20was%20passed%20over,Committee%20from%201993%20to%201995

Madison, J. (1798, April 2). James Madison to Thomas Jefferson [letter]. Founders Online: National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-30-02-0161

Reuters. (2025, February 4). Trump says he wants Ukraine to supply US with rare earths. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/trump-says-he-wants-ukraine-supply-us-with-rare-earths-2025-02-03/#:~:text=By%20Reuters,or%20just%20to%20rare%20earths

Rogers, K. (2026, January 6). Stephen Miller offers a strongman’s view of the world. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/06/us/politics/stephen-miller-foreign-policy.html

Troianovski, A. (2026, January 3). Trump long wanted to ‘Take the Oil.’ He says he’ll do it in Venezuela. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/03/us/politics/trump-venezuela-oil.html

Worldometer. (n.d.). Oil reserves by country. Retrieved January 7, 2026, from https://www.worldometers.info/oil/oil-reserves-by-country/#google_vignette

Zurcher, A. (2025, April 14). What Trump really wants from Canada. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c15vl99dw0do

[1] “We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else, but we live in a world, in the real world … that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power … These are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time” (as quoted in Rogers, 2026).